By Xuwen Luo

Abstract

Both India and China have been promoting Public Private Partnership in delivering infrastructure in various sectors. This paper examines their current infrastructure condition both in terms of quality and investment and therefore understands the driving factors of them using PPP. It compares and contrasts the characters of PPPs in India and China. India prioritizes in transport and energy while China puts its emphasis in public services. SOEs have a bigger presence in PPPs in China while foreign investors have more space in India. The main reason for India using PPP is the gap between government fiscal capacity and the increasing infrastructure demand; while in China, the key is innovation, in the sense that private sector has better technology and management skills in tackling sophisticated issues such as water treatment and elderly care. China takes a top-down approach in the promotion of PPP while India, in the national level, also takes a top-down approach but has to take a bottom-up approach in the state level. The paper also discusses some of the major challenges for both countries including human resources, regulatory and legal framework and financing gap. The author is cautiously optimistic about the future of PPPs in both countries given the fact that both governments having been taking actions to address the challenges although these challenges are quite daunting.

Infrastructure in India and China

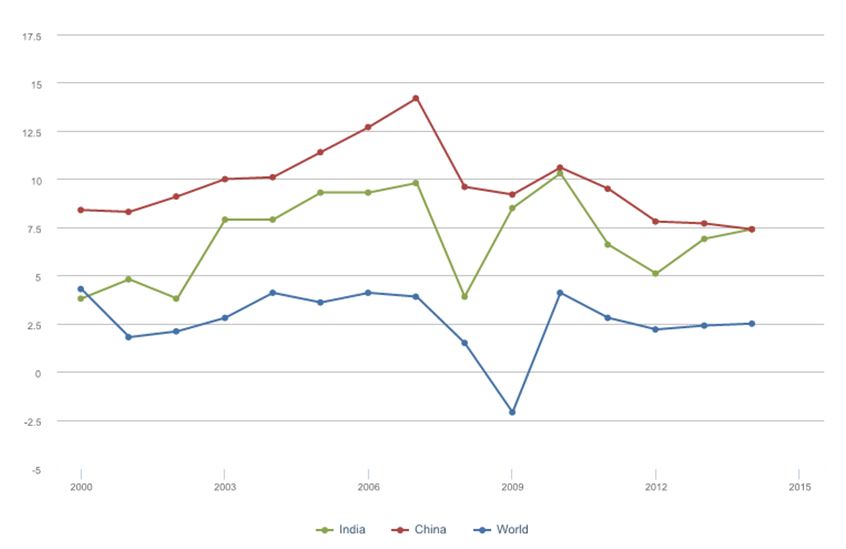

Both India and China have been economic engines of world economy in the 21st century. China has been growing at a rate above 7.5% (except for 2014) with a trend of deceleration after 2008 financial crisis. India has been growing mostly above 5% per year. Since 2012, its growth has been increasing back to its pre-crisis level, which was close to 10% per year, according to the World Bank. Both of them have been growing at rates much higher than the world average. (Exhibit 1)

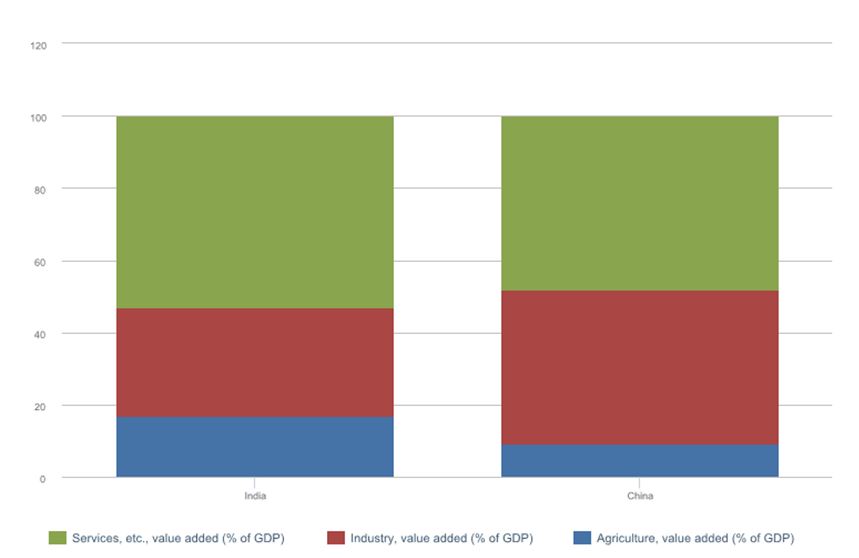

However, the driving factors are not different in these two countries if we breakdown different sectors’ contribution to GDP. As shown in Exhibit 2, India has a larger service sector while China has a much larger industry sector. Agriculture’s contribution to Indian GDP almost doubles the one to Chinese GDP. In other words, Indian economy is both more agriculture intensive and service oriented than the Chinese economy, which is driven 42.6% by the industry sector. This phenomenon can be the cause and the result of the lack of infrastructure in India, in comparison with China.

According to Logistics Performance Index designed by the World Bank, India ranks the 54th with an infrastructure score of 2.88 while China ranks the 28th with 3.67 as its infrastructure score.(1) Both countries have extensive transport network, nonetheless it is the quality of the infrastructure that makes the difference. India has a road network of 4,689,842 km, which includes 79,116 km of national highways and expressways, 155,716 km of state highways, and 4,455,010 km of other roads. The 4,455,010-km other roads are largely unpaved. In comparison, China has 4,106,387 km of roads, among which 652,497 km is unpaved.(2) Similarly, the railroad systems are similar in size while different in quality.(3) In terms of internet coverage, China has 46.8 internet users per 100 people while the number in India is 18.(4) Estimates suggest that the lack of proper infrastructure pulls down India’s GDP growth by 1-2% every year.(5)

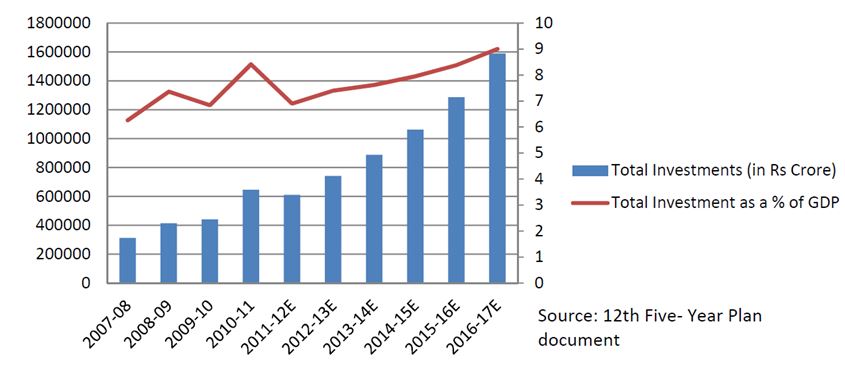

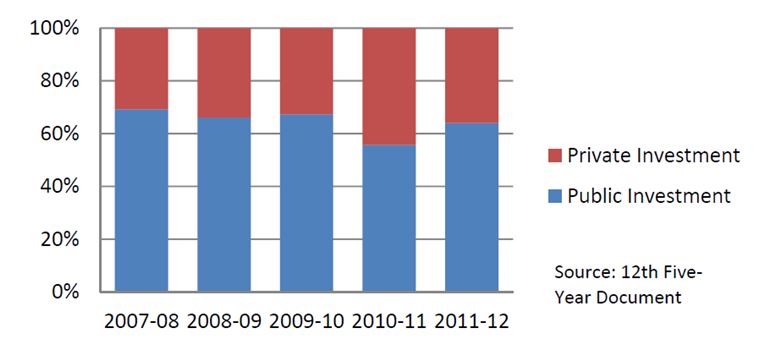

Despite the difference in infrastructure development, both countries have been thirst about the investment to infrastructure sector. In Indian case, the total investment in infrastructure, which includes roads, railways, ports, electricity and telecommunication, oil gas pipelines and irrigation, is estimated to have increased from 5.7% of GDP in the base year of the 11th Five Year Plan (2006) to about 8% in the last year (2011). The pace of investment has been particularly buoyant in telecommunication and oil and gas pipelines while falling short of targets in electricity, railways, roads and ports. The 12th Five Year Plan expects a 7-9% share of GDP infrastructure investment, which worth approximately one trillion USD. (See Exhibit 3) Public sector has been dominating in infrastructure investment. (See Exhibit 4) However, this one trillion investment gap is not going to be covered entirely by public sector given the sheer amount. It is expected that there would be a higher participation from the private sector.

In the Chinese case, besides the similar reason of huge infrastructure demand, hence high level of funding required, there is another factor worth noticing: local government debt. According to the National Audit Office, in 2011, the level of local government debt was 10.7 trillion RMB. (1.70 trillion USD (6)) in 2013, it reached to 17.9 trillion RMB (2.84 trillion USD) which was one-third of China’s GDP. More than half of the local government debt was targeted to infrastructure development.(7) In spite of the debt level, the pace of urbanization in China is not going to slow down. The urbanization rate is expected to reach 60% by 2020. In other words, there will be approximately 100 million people coming urban residents and their demand for infrastructure and urban public services has to be met. Therefore, the involvement of private sector would become particularly valuable in this context.

Public Private Partnership (PPP), often times representing the mobilization of private capital towards infrastructure and public services, is not a brand new notion for neither of the countries. However, because of the reasons discussed above, it has become increasingly popular in public discourse.

Public Private Partnership and the Experiences of India and China

PPP is a collaborative organizational structure supported by public, private or non-profit partners who agree to share risks, resources and decisions in developing and implementing certain projects. It usually happens in the case that neither the government nor the private sector can complete the task on its own. The public partners in a PPP are government entities, including ministries, departments, municipalities, or state-owned enterprises. The private partners can be local or international and may include businesses or investors with technical or financial expertise relevant to the project. Increasingly, PPPs may also include nongovernment organizations (NGOs) and/or community-based organizations (CBOs) who represent stakeholders directly affected by the project. Effective PPPs recognize that the public and the private sectors each have certain advantages, relative to the other, in performing specific tasks. The government’s contribution to a PPP may take the form of capital for investment, a transfer of assets, or other commitments or in-kind contributions that support the partnership. The government also provides social responsibility, environmental awareness, local knowledge, and an ability to mobilize political support. The private sector’s role in the partnership is to make use of its expertise in commerce, management, operations, and innovation to run the business efficiently. The private partner may also contribute investment capital depending on the form of contract.(8) In a time of limited government resources and growing challenges, PPPs can provide solutions to complex problems.

It is believed that China started its first PPP project in 1995 which was Laibin B power plant in Guangxi, a southwestern province. After that, there were several power plant and water utilities built through Build-Own-Transfer (BOT)(9). This is the first wave of PPP in China, which was under the principle of attracting foreign direct investment (FDI) and was dominated by the leadership of the then National Planning Commission (now the National Development and Reform Commission, or NDRC). However, the first wave of PPP did not move from the experimental stage to a larger scope. In 2004, the then Ministry of Construction (now part of Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development) took the lead and created the second wave of PPP. More government entities were involved in this second wave as opposed to the sole leadership of the Planning Commission. Both domestic and foreign capital, SOEs and private companies are treated equally. However, the purpose of PPP was still mostly shredding the risks of some tough projects to the private sector. Because of the capacity and size of SOEs, private capital did not gain much from the second wave either. The active participation of SOEs created the problem of an opaque oversight structure. Public sector being both the regulator and the player has been one of the biggest issues in Chinese PPP experience. The year 2014 started the third wave of PPP, which is the current wave. NDRC and the Ministry of Finance took the lead after the 18th Party Congress confirmed “the permission of social capital participating in the investment and operation of urban infrastructure through the means of concession.”(10)

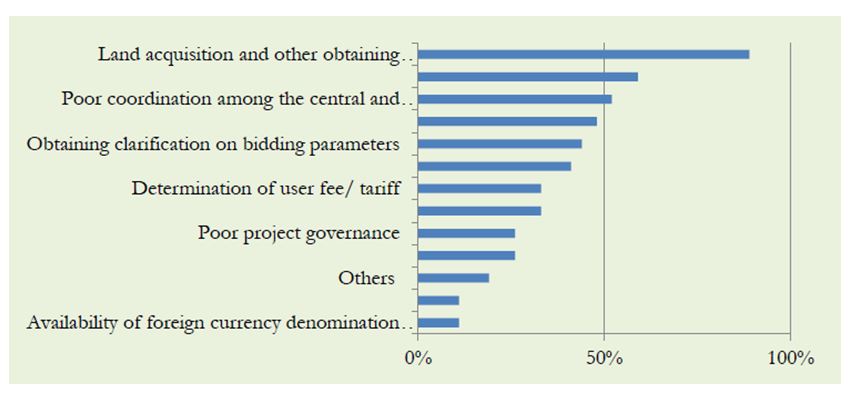

Private participation in Infrastructure is not new to India. For instance, prior to obtaining independence from British rule in 1947, 65% of power generation was done by private companies. After independence, a wave of nationalization swept across the country, and the role of the private sector in infrastructure provision was soon marginalized. For the most part, private firms were limited to being contractors, and in some cases operators of infrastructure services, particularly in key infrastructure segments such as transportation, power, telecommunications and urban infrastructure.(11) After the 1991 economic reform, PPP was introduced to India through telecommunications. The biggest sector adopting PPP is transportation. 2005 survey showed that 74% of all Indian PPP infrastructure projects were in the roads and bridges category, at the national level.(12) India had some unpleasant experience with PPP, mostly due to issues of land acquisition, delays in forest and environmental clearance, etc. However, PPP has become popular again due to the amount of infrastructure demand. The 12th Five Year Plan targets private participation in infrastructure at 50%.(13)

Current Conditions from a Comparative Perspective

The current PPP practices in India and China are different in terms of sector priority, major participators, leadership and purpose of using PPP.

India focuses almost exclusively in transport and energy sector. In 2014, it had 16 projects in transport and 14 in energy; none were in water and sanitation.(14) The Chinese case is almost the opposite. Although transport took a large part of the infrastructure construction in China, it has been performed mostly through participation of SOEs. In the current context of increasing urbanization rate and environmental degradation, water becomes the most important topic in Chinese PPPs with pure private investment. In 2014, China has 20 water projects in World Bank’s PPI database, which is the highest among all countries.

As mentioned very briefly, the presence of SOE is another difference between these two countries’ PPPs. China has been having the issue of defining PPP since most of the capable players are in fact state owned. The Chinese terminology for PPP translates literally as “Government-Social Capital Cooperation”, indicating that the door will keep being open for SOEs. The problem of the possibility of government authorities, having special relations with the SOEs, wearing two hats as both the regulator and the project participant has not been solved. This goes in the same line of the long ongoing reform within the Chinese government of the transition from an approval entity to a service and regulating entity.(15) India, though also has a presence of SOEs, suffers from this problem to a less extent.

In terms of foreign participation, there are some similarities and differences. Both countries have large diaspora communities. In the Chinese case, most of the PPP projects in the first wave and second wave were participated by Chinese diaspora particularly businessmen originally from Southern China, which partially explained why first wave projects were heavily concentrated in the South. Modi has campaigned around North America and Europe to promote India and attract FDI, particularly targeting the Indian diaspora. The approaches China and India take are different. China tends to go with the joint venture approach in order to secure the investment from fleeing the country and gain technological know-how with a long-term goal of establishing indigenous capacity at competitive level. India recently lifted the bar of foreign participation in PPP project to 100%.(16) In other words, foreign capital can now go directly into a project without a local partner.

In terms of leadership, China takes a top-down approach in promoting PPP while it is a mixture of top-down in the national level and bottom-up in the state level in the Indian case. NDRC and Ministry of Finance (MoF) took the lead in China. An office devoted to PPP was created in 2014 under the MoF.(17) NDRC has created two batches of PPP projects open for bidding. It is worth noticing that most of them are in urban services, such as water utilities, sewage treatment waste management, environmental rehabilitation, etc. Furthermore, the sectors of public health and elderly care are two new sectors starting to use PPP.(18) Chinese government was very cautious about social PPPs, those are sophisticated in operation and need constant government subsidies,(19) like hospitals. However, they are moving into this field currently.

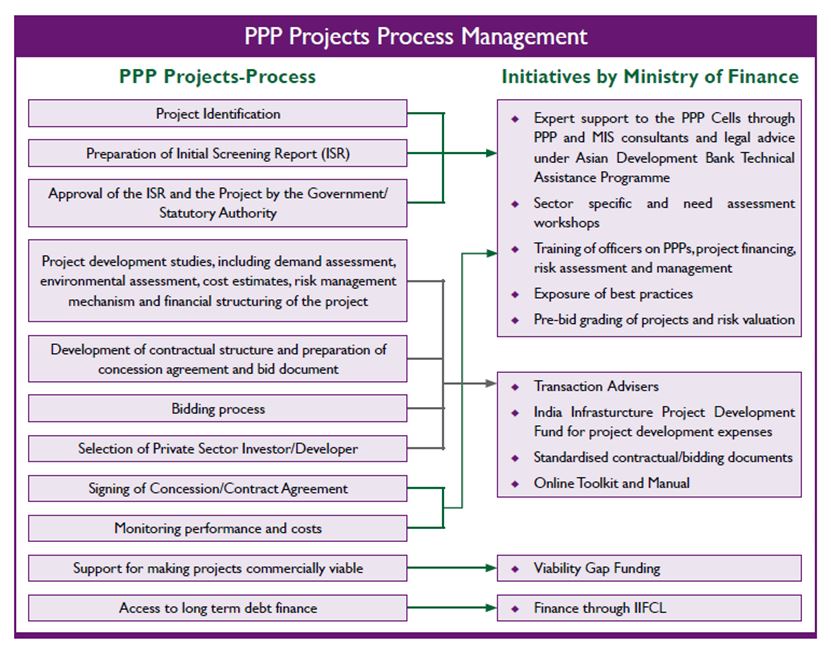

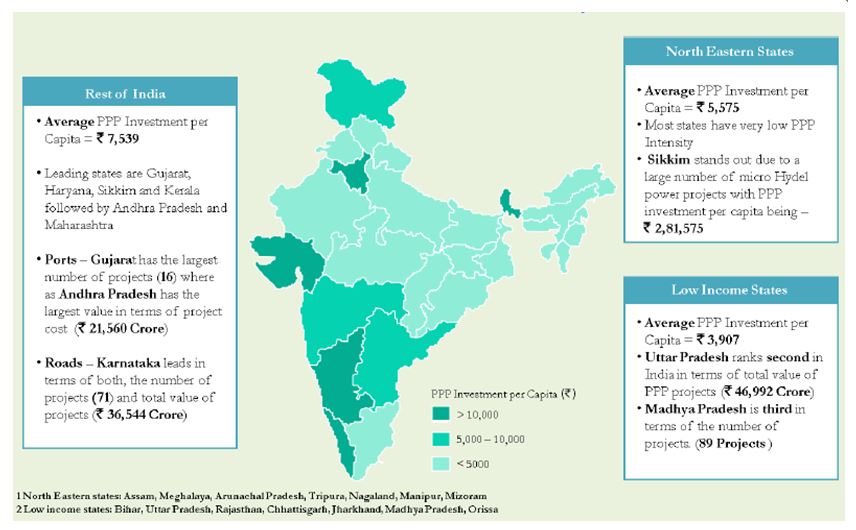

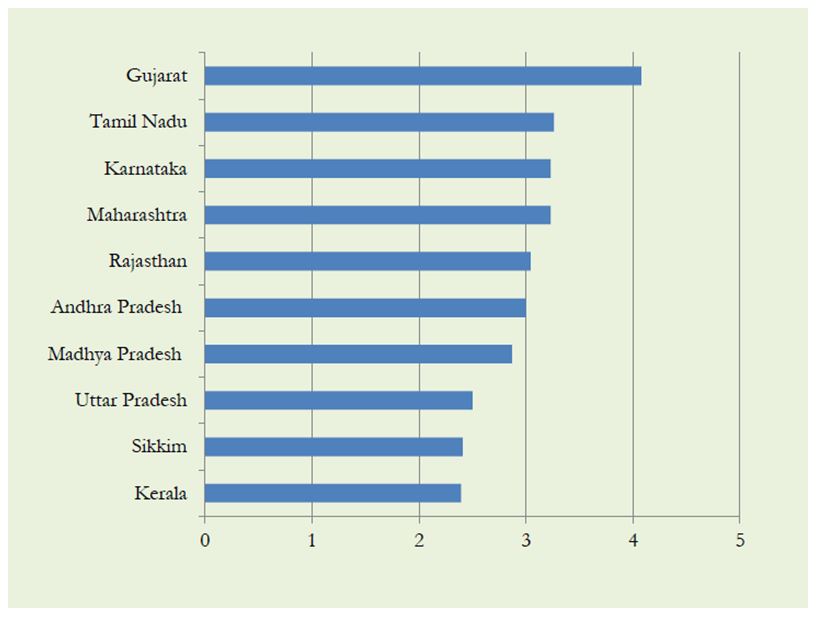

In the Indian case, the MoF is the one who takes the lead as well. It set up Public Private Partnership Appraisal Committee (PPPAC) and the website pppinindia.com devoted exclusively to PPPs, which serves as the virtual market place for PPP projects. To address the financing needs of these projects, various steps have been taken like setting up of India Infrastructure Finance Company Limited (IIFCL) to provide long tenor debt to infrastructure projects; and launching of a Scheme for Financial Support to PPPs in Infrastructure to provide Viability Gap Funding (VGF) to PPP projects. (Exhibit 5)(20) However, being a democratic federal system, states play important roles in attracting infrastructure investment. Different states have different investment climates and enabling environments. Therefore, some of them have gone further in attracting private investment while some of them have lagged behind significantly. Gurajat is the most PPP friendly state, notably, where Prime Minister Modi led as a governor. (Exhibit 6 & Exibit 7) Gurajat’s success is mainly due to its predictability, transparency and fast-track bureaucracy. For instance, Gujarat is one of three states in India (the others being Madhya Pradesh and West Bengal) with a mandate that authorities issue registrations for value-added tax (VAT) and professional tax in a single day. Transparency in matters of land ownership and regulations is another strength. Twenty states in India have a so-called land bank (land available for investors), but Gujarat is one of only a few where investors can check the availability of industrial land through publicly accessible geographic information system maps.(21) However, it is not easy to replicate its success owing to varying political priorities. There have already been significant policy differences between the BJP-led central government and non-BJP-linked states, and these will continue to remain a feature of Indian politics.

In addition, as discussed above, the ultimate purposes of promoting PPPs are different in China and India. The Chinese wants PPP to fill up the innovation gap while the Indian needs extra funding. It is this fundamental difference that leads to the difference in priority, being public services in China and transport and energy in India. This is due to the different development stages of the two countries.

Conclusion: Major Challenges and Steps Taken

PPP is not a panacea for the government to shred risks to private sector of even build up infrastructure for free, as some people believe both in India and China. There are some common challenges of implementing PPP in both countries, with their distinctive characters, which can be summarized as human resources, legal and regulatory framework and financing gap.

In terms of human resources, both countries are lacking qualified personnel in the government who understand the intricacies of PPP projects and are sophisticated enough to negotiate against the private sector. In the case of India, IAS officers do not stay in one posting long enough(22) to implement polices consistently and build up long-term relations with private sector partners, which makes the existing lack of trust between the private sector and the public sector even worse. In the Chinese case, bureaucracy and clientelism are driving young talents with innovative minds away from the government. The ongoing anti-corruption campaign is make this brain-drain condition even worse because of the uncompetitive compensation the government is able to provide. The major issue is the transition of mindset both in the public sector and the private sector, being the previous thinks the latter is notoriously greedy and the latter regards the previous as hopelessly backward. This transition of mindset can only happen if the channels of human resources are more streamlined, hence the communication.

Strong legal and regulatory framework is the key to PPPs since these are essentially businesses about contracts. If there is not an environment to enforce contract, then PPP will by no means flourish. Both India and China understand its significance and have been putting significant efforts into this issue. India has created standardized contractual documents such as sector specific Model Concession Agreements, which lays down the standard terms relating to allocation of risks, contingent liabilities and guarantees as well as service quality and performance standards, and standardized bidding documents such as Model Request for Qualifications and Model Request for Proposals.(23) The Chinese has been working on the legislation on PPP and concession operations. Dispute settlement mechanism is one of the key issues that will be addressed.(24)

A lack of bankable projects and a lack of financing facilities create a double-whammy condition in both of the countries. India tries to solve this problem by creating IIFCL, to provide more long-term debt financing facilities by raising funds from domestic and overseas markets(25) on the strength of sovereign guarantees and lowering borrowing costs. The exposure of IIFCL in one project is limited to 20% of the total project cost which translate to approximately 30% of the total debt in order to mobilize private capital.(26) In the Chinese case, its PPP projects are mostly financed by short-term bank loans backed by sovereign or local government guarantees. However, the discussion of opening up the local government bond market has been going on and it is expected to happen in the near future given the level of local government debt and the danger of off-the-balance-sheet local government financing vehicles. A deeper bond market would provide more financing options with more accommodative terms.

These major challenges are not easy to tackle. However, both the Indian and the Chinese seem to understand these issues well and have been putting serious efforts into them.

Appendix

Source: World Development Indicator, the World Bank

Source: World Development Indicator, the World Bank

Source: Ministry of Finance, Department of Economic Affairs

Source: Athena Infonomics India

Source: Athena Infonomics India

Source: Athena Infonomics India

Notes

(1) http://lpi.worldbank.org/international/global?sort=asc&order=Infrastructure#datatable

(2) https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2085.html

(3) http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IS.RRS.TOTL.KM

(4) http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.NET.USER.P2

(5) Geethanjali Nataraj: “Infrastructure Challenges in India: the Role of Public-Private Partnerships”, p.1

(6) Exchange rate used in this paper: 1USD=6.3CNY

(7) http://www.audit.gov.cn/n1992130/n1992150/n1992500/n3432077.files/n3432112.pdf

(8) Asian Development Bank: Public Private Partnership Handbook, p.1

(9) Build-Own –Transfer: the private developer is responsible for the construction of the project and gets concession for operating it and taking a certain percentage (even 100%) of the profits. In the end of the concession, the private sector hands over the ownership to the government authority. Details are negotiated among stakeholders on case-by-case basis.

(10) The original text in Chinese: “允许社会资本通过特许经营等方式参与城市基础设施投资和运营”

(11) Ashwin Mahalingam: “PPP Experiences in Indian States: Bottlenecks, Enablers and Key Issues”, p.2

(12) http://infrastructure.gov.in

(13) http://planningcommission.gov.in/plans/planrel/12thplan/pdf/12fyp_vol2.pdf

(14) The World Bank: 2014 Global PPI Update, p.9 http://ppi.worldbank.org/~/media/GIAWB/PPI/Documents/Global-Notes/Global2014-PPI-Update.pdf

(15) The notion of “service-oriented government” (服务型政府) was first mentioned by Primer Wen in 2004, more than a decade from today, http://dangshi.people.com.cn/GB/221024/221027/14907461.html

(16) Indian Ministry of Finance: “PPP, Creating enabling environment for state projects”, p.3

(17) http://jrs.mof.gov.cn/ppp/

(18) http://tzs.ndrc.gov.cn/zttp/PPPxmk/

(19) Economic PPPs v.s. Social PPPs: Economic PPPs are usually more straight-forward in its operational stage and its revenue generation structure is clearer. Often times, it does not need government subsidy. Social PPPs demand government subsidy and its operation is much more sophisticated. A typical economic PPP would be a toll road and a good example of social PPP would be a hospital.

(20) Indian Ministry of Finance: “PPP, Creating enabling environment for state projects”, p.3

(21) Economist Intelligence Unit, “Gujarat set to drive the government’s push for competition”

(22) http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/68-of-IAS-officers-have-average-tenures-of-18-months-or-less/articleshow/28203370.cms

(23) Indian Ministry of Finance: “PPP, Creating enabling environment for state projects”, p.3

(24) http://finance.china.com.cn/roll/20151126/3465296.shtml

(25) IIFCL has a subsidiary registered in London to handle transactions in overseas markets.

(26) http://blogs.worldbank.org/ppps/innovative-financing-case-india-infrastructure-finance-company

References

[1] International Institute of Sustainable Development, “Public-Private Partnerships in China”, 2015

[2] G. Nataraj, “Infrastructure Challenges in India: The Role of Public-Private Partnerships”, 2014

[3] The World Bank, “2014 Global PPI Update”, 2014

[4] Asian Development Bank, “Public-Private Partnerships in Urbanization in the People’s Republic of China”, 2014

[5] Junhe Partners, “PPP in China: Development and Implementation” (PPP模式在中国的发展与实践), 2014

[6] A. Mahalingam, “PPP Experiences in Indian States: Bottlenecks, Enablers and Key Issues”, Indian Institute of Technology, 2013

[7] S. Sampath, “Challenges and Issues in Structuring and Managing PPPs: What should the public sector know about?”, Workshop on Mainstreaming PPP in the Urban Sector, Commonwealth Secretariat, 2012

[8] Athena Infonomics India, “Public Private Partnership in India: Lessons from Experiences”, 2012

[9] R. R. Shaik et al., “Comparative Analysis of Infrastructure PPP in BRICS Nations”, Indian Institute of Management, 2011

[10] L. Lakshmanan, “Public-Private Partnership in Indian Infrastructure Development: Issues and Options”, Reserve Bank of India Occasional Paper, 2008

[11] Indian Ministry of Finance, “Public Private Partnerships: Creating an Enabling Environment for State Projects”, 2008

[12] Asian Development Bank, “Public-Private Partnership Handbook”, 2005

[Editor’s view on the paper]

This paper makes a comparative analysis of public private partnership (PPP) in infrastructure in India and China. Through four parts, the comparison refers to various aspects, including infrastructure situations in the two countries, their historical experiences of developing the mode of PPP in infrastructure, respective characteristics of current conditions in this field, and the different challenges that India and China are facing. With a reasonable structure and accurate and abundant data, the author presents us a comprehensive comparison on PPP in infrastructure in the two countries, which both attach great importance on infrastructure development. However, lack of space forbids further discussion in some fields, and for each point of comparison, the author only gives a brief introduction and analysis. It is believed that wider and deeper issues can be discussed regarding each point that is mentioned in the comparative analysis. Besides, comparison should not be the whole content of the analysis, and beyond fundamental comparison between India and China, we can further discuss whether the two countries can learn from each other, and whether they can cooperate in this field in the future despite their huge differences.