For all the disappointment among investors since Prime Minister Narendra Modi swept to power nearly two years ago, India’s farmers have been even more frustrated.

Back-to-back droughts, meager increases in guaranteed crop prices and neglect of a rural jobs program all led to rising discontent in villages that saw Modi as an economic savior in 2014. He hit a low point in November, when his ruling party got crushed in Bihar, India’s third most-populous state.

Modi fired back on Monday with a pro-farmer budget that aimed to reverse the tide and set his party up for better showings in a slew of state elections before the next national vote in 2019. In doing so, he sought to take away a key opposition attack: That his government favors the rich over the poor.

“It’s a very political budget,” Harsh Pant, professor of international relations at King’s College London, said by phone. “I don’t think Modi ever considered himself pro-corporate, but that was the way he was being perceived by the opposition and media. This was a major attempt by him to change that narrative.”

Farmer Relief

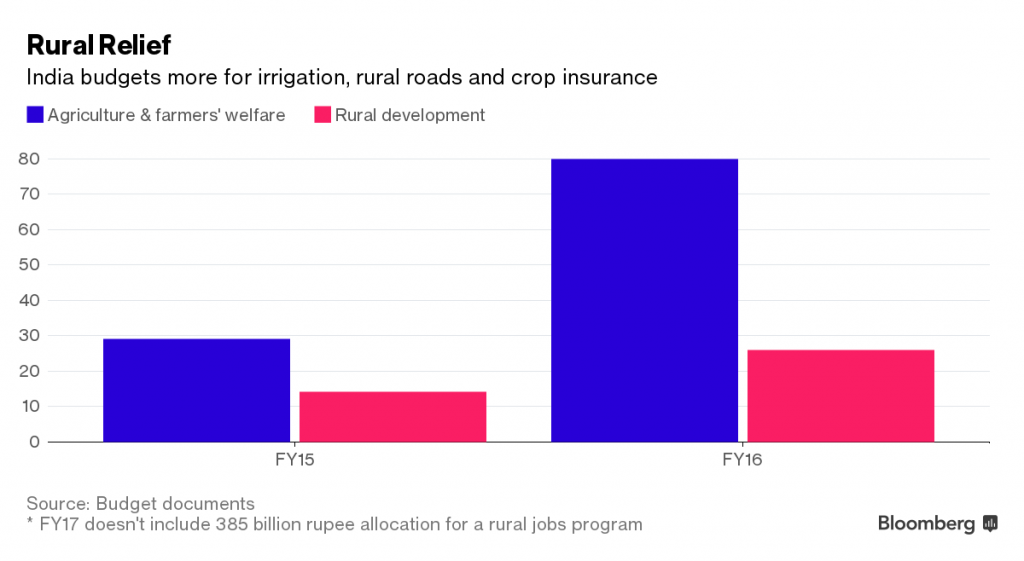

Finance Minister Arun Jaitley wasted no time getting to the point. The first section of the nearly 90-minute speech was titled “Agriculture and Farmers’ Welfare” followed by “Rural Sector.” He called farmers “the backbone of the country’s food security” and vowed to double their income by 2022.

A slew of other measures followed aimed at the 70 percent of Indians who live outside of the nation’s megacities: Expand irrigation, revamp crop insurance, build more rural roads, improve groundwater resources. Every village would have electricity by May 2018. Every impoverished household would have cooking gas. Every poor family would get better health care.

To help pay for the farmer welfare programs, Modi raised taxes on services that are mostly used by city dwellers.

“The biggest focus of this budget is village, poor, farmer, women and youth,” Modi said on Monday. “I would like to assure the countrymen that this budget is close to your dream.”

At the same time, Modi also managed to please a financial community that had become increasingly skeptical after 21 months of setbacks. For the first time since he took office, low expectations seemed to help him out.

Rate Cut Coming?

Modi stuck with the fiscal deficit target and reduced net borrowings, creating space for private companies to access credit markets. That should please central bank Governor Raghuram Rajan, who had warned that an undisciplined budget may lead to higher bond yields.

While India is the world’s fastest growing major economy, it’s also showing signs of weakness. Exports have declined for 14 months and credit growth is at the lowest level in at least 15 years. The banking system is saddled with stressed assets, and power producers are crippled with debt. India’s stocks, rupee and bonds are among the world’s worst performers this year.

Economists are now expecting Rajan to reward Modi with another rate cut, possibly before the next scheduled review on April 5. Jayant Sinha, India’s deputy finance minister, said on Monday that “we have very limited space” on the fiscal side to boost growth but “monetary space is not limited.”

Modi Stumbles

The budget “reflects the realities of our country,” Sinha said in an interview in New Delhi. “We have to be bimodal: Pro-poor on the one hand and pro-market on the other hand.”

That nuance is a stark change from when Modi took office. The expectations were sky-high from all sides: Investors wanted big-bang economic reforms, his Hindu nationalist followers wanted a cultural revolution and poor villagers wanted a better life.

Modi stumbled out of the gate, with his first budget largely resembling those of the ousted Congress-led government. He balked on scrapping a retroactive tax that spooked investors and left subsidies untouched.

When he did push for big reforms, such as making it easier to acquire land, he opened the door for the opposition to paint him as a “suit-boot” government that favors the business elite over the poor. In the face of opposition, he withdrew the bill. Proposals to ease restrictive labor rules were also shelved.

Bihar Pivot

On the heels of a crushing defeat in Delhi last year, the Bihar election marked a turning point. Modi’s opponents united against his Bharatiya Janata Party and won 73 percent of seats, dealing a major blow to his plans to wrest control of the upper house of parliament, where a landmark goods-and-services tax has been stalled for months.

Modi unsettled investors in a January speech to an economic forum in which he compared subsidies for the poor with tax breaks for the rich. “Why is it that subsidies going to the well-off are portrayed in a positive manner?” he asked.

“The BJP has been politically prudent after the defeat in Delhi and Bihar,” said Sandeep Shastri, pro vice chancellor at Jain University in the southern city of Bengaluru and an author on Indian politics. “They have realized the importance of responding to the rural hinterland.”

Modi’s opponents saw the budget as reinforcing their view that his government is big on slogans and weak on real reform. Palaniappan Chidambaram, Jaitley’s predecessor as finance minister, credited the crash in oil prices for doing all the hard work of fiscal consolidation.

Two-Term Government

“What is the one big takeaway for the average citizen?” Chidambaram said. “It is that there is no Big idea.”

For Modi, though, the budget reflects a new political reality. He’s now focused less on impressing global investors and more on winning over the rural masses who will determine whether he gets a second term in 2019.

“This government has always looked at itself as a two-term government,” said Pant from King’s College. “Despite the criticism he will receive from the market reformers, he will be satisfied that he has done what he should have from a political perspective.”