The Chinese renminbi is likely to get a big stamp of approval from the International Monetary Fund next week. On Monday, the IMF’s executive board will vote on whether to add the RMB, as it’s commonly abbreviated, to its basket of reserve currencies.

Essentially, the International Monetary Fund has its own artificial currency – a mash-up of the U.S. dollar, the Japanese yen, the euro, the pound sterling – and perhaps soon – the RMB as well.

“People can think of it as index, just like Dow Jones Index,” said Steve Hanke, a professor of applied economics at Johns Hopkins University. “That’s made up of 30 stocks and the prices of those stocks change and the index changes.”

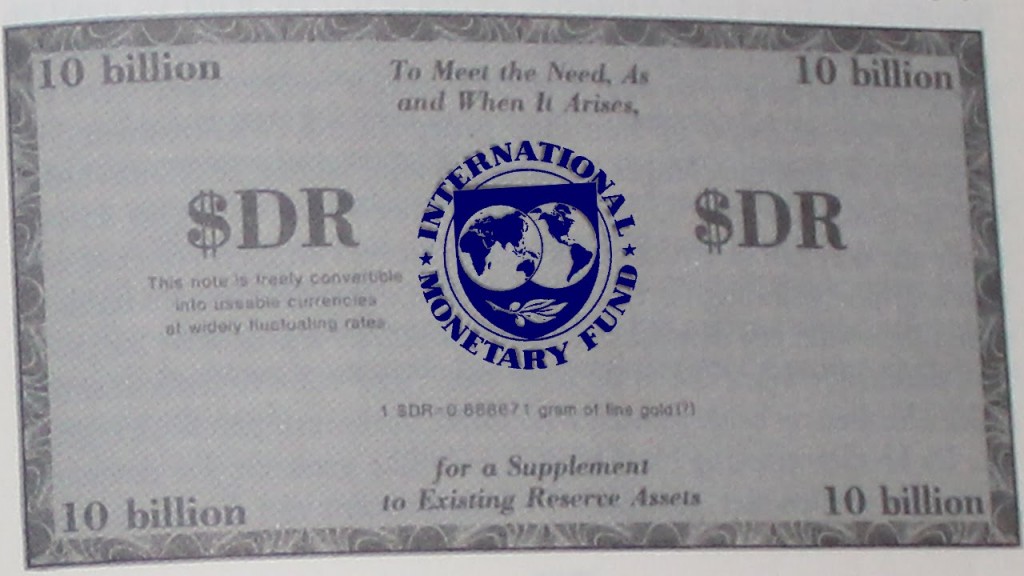

IMF member countries receive allocations of this special IMF currency, known as Special Drawing Rights.

“One Special Drawing Right today is worth about $1.38,” said Hanke. “The unit is the way the IMF keeps its books. It’s not keeping them in dollars, it’s keeping them in SDRs.”

By doing its accounting in SDRs, the IMF is better covered in case one of its composite currencies dramatically rises or falls in value. Countries can use their SDRs however they want, such as to plug budget shortfalls or pay debts.

“Currency strategists like myself, we calculate how much countries like Greece might owe the IMF in euros,” explained Marc Chandler, the global head of currency strategy at Brown Brothers Harriman. “But in fact, the IMF loans Greece SDRs.”

In a paper released earlier this month, IMF staff determined that the RMB met the requirements to be included and recommended the board approve its addition.

Hanke thinks that once the RMB gets this seal of approval from the IMF, countries’ central banks may start adding RMB to their reserves, their rainy day funds. That would send capital flows into China, which Hanke said would be a good thing at a time when lots of Chinese are investing outside the country.

But Chandler doesn’t think the RMB’s inclusion in the SDR will significantly change demand for the currency in the short term.

“Japan has been in the SDR since it was launched back in 70s,” he said, by way of example. “Its share of world trade is minimal, its share of global bonds issued in yen is very small, and its share as global reserve currency is also very small.”

Getting into the SDR doesn’t mean the RMB will begin rivaling the dollar, he said. What it does signal is respect for China and its impact on the global economy.

“It’s a sign that China has arrived, that it’s recognized as one of the major financial powers,” Chandler said.

“Symbolically, this is really a big deal for China,” agreed Eswar Prasad, a professor at Cornell University and former China head at the IMF.

Prasad also doesn’t expect this short-term change for the RMB after its inclusion in the SDR. But he said it’s a significant validation of the financial reforms China has pushed in recent years, many of which were partially or largely motivated by earning this prized status.

“The reason it matters is because it makes it easier for the Chinese government open up and develop its financial markets,” he said. “The slogan was basically that China is a big and powerful country and it needs to have a big and powerful currency.”