A second deal to take over Transaero has fallen through, leaving little hope that the airline can avoid bankruptcy.

After two months of oscillating between bankruptcy and promises from other air carriers to come to its rescue, Russia’s second biggest airline Transaero appeared to have had its fate sealed this week when a second takeover deal fell through.

Vladislav Filyov, co-owner of S7 Airlines, which was in the process of buying a controlling 51 percent stake in Transaero, announced Monday he was pulling out of the deal.

It was the second time a major airline had tried and failed to save Transaero from collapsing under 260 billion ruble ($4 billion) debt, and though S7 said the next day the deal could possibly be resurrected, analysts polled by The Moscow Times say there will be no third attempt.

Transaero has nothing to offer to potential buyers right now: It’s banned from flying, its major international destinations have been given to Russia’s flag carrier Aeroflot, and it’s saddled with debt. Bankruptcy is the only option left, experts agree.

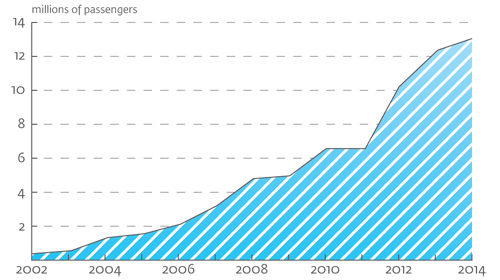

Until recently Transaero operated flights to 260 Russian and international destinations, and accounted for 14 percent of the domestic aviation market. From January to July this year, 7.5 million passengers flew with Transaero, while the 2014 total was 13.2 million.

The company’s finances had weakened due to the recession and sharp devaluation of the ruble, which have depressed demand for travel and raised the cost of airplane leasing agreements, which are often denominated in dollars.

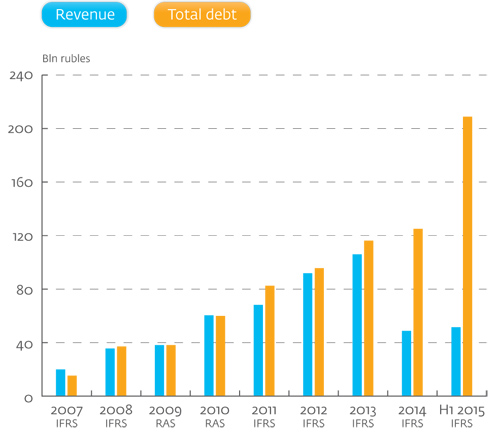

Transaero’s 260 million ruble debt includes 150 billion rubles ($2.4 billion) owed in leasing obligations and 20 billion rubles ($325 million) owed to airport management and fuel companies. The airline also has multibillion-ruble loans from a clutch of major Russian banks, according to the TASS news agency.

On Sept. 1, Aeroflot announced an offer to purchase a 75 percent stake in Transaero for a symbolic 1 ruble in order to save it from going under. The deal fell through a month later, when the company’s stakeholders failed to produce the shares by the deadline of the deal set for Sept. 28.

Government officials and Transaero’s creditors — state-owned banks VTB (owed 12.7 billion rubles) and Sberbank (owed 6 billion rubles) among them — promptly started contemplating its bankruptcy, and Transaero was banned from selling any more tickets. In less than a month, it was stripped of its license and barred from flying.

On Oct. 20, the airline appeared to have been thrown a lifeline when S7’s Filyov announced he had agreed with Transaero’s major stakeholder Alexander Pleshakov to buy a stake of at least 51 percent in the company.

In an interview with the Kommersant FM radio station two days later, Filyov confidently called it a done deal, but two weeks later his wife Natalya, the co-owner of S7, said the deal had been called off due to the fact that Pleshakov had failed to produce 51 percent of unencumbered shares.

The current shareholders of Transaero simply don’t have 51 percent of unhindered shares, a spokesperson for S7’s owners told The Moscow Times in written comments.

“Some of these shares are also the subject of lawsuits, so completing the deal in the current situation is not possible,” the spokesperson said.

Pleshakov said in a statement posted on Twitter by his wife Olga, Transaero’s chair of board of directors, that Filyov had violated the conditions of their agreement, according to which Pleshakov had 60 days to produce a 51 percent stake.

“Filyov’s announcement of ‘quitting the share purchase deal’ before the 60 days expired (it’s been only 12 days) is a clear violation,” Pleshakov wrote on Twitter, adding that he could have bought more shares in the 60 day period and that Filyov was well aware the shares were encumbered.

The Moscow Times couldn’t reach Pleshakova for a comment on whether her husband plans to insist on seeing the deal through, or what future Transaero might face.

A spokesperson for S7 said Tuesday that the company would return to the negotiating table “if representatives of VTB decide to release Transaero’s shares and Pleshakov manages to put together a 51 percent stake.”

Spokespeople for VTB, Transaero’s main creditor that holds 25 percent of the company’s shares in guarantees, neither confirmed nor denied speculation that it had blocked the deal.

“The bank will try to obtain what is owed by the company … by legal means,” VTB said in written comments sent to The Moscow Times.

It was the government that tried to save Transaero, says Andrei Kramarenko, an expert from the Institute for Transport Economy and Policy, a Moscow-based think thank.

“It was [Deputy Prime Minister Igor] Shuvalov who initiated the deal with Aeroflot,” he said. “[The government] took efforts to keep Transaero afloat, avoid price hikes and keep competition on the market,” but Aeroflot couldn’t benefit from the deal and canceled it on a technicality, he said.

Transaero’s bankruptcy would mean the dismissal of 11,000 employees. Some analysts have predicted dramatic price hikes for plane tickets, and have warned that smaller banks which loaned money to the airline could also get into financial troubles.

Transaero was unsalvageable from the very beginning: It had driven itself into multimillion-ruble debt, said Oleg Panteleyev, head of analysis at the Aviaport news agency.

“Saving Transaero as it is meant multiplying losses,” said Panteleyev. “That’s why even the salvage options involved restructuring it and cutting a major part of it,” he added.

“[Its fate] depended mostly on creditors. If they could have agreed with each other, there would have been no need for either the first savior or the second one. But they had completely different interests … some of them opposing, and agreement hadn’t been reached,” he told The Moscow Times.

Both Kramarenko and Panteleyev agreed that bankruptcy was inevitable at this point.

“Transaero killed itself. You can’t fly for such a long time at a loss,” Kramarenko said.