Engulfed by political and economic crises, Brazil can ill afford to be beset by more problems.

Yet that’s exactly what is happening after its southernmost state of Rio Grande do Sul defaulted on a 280 million real ($80.9 million) payment to the federal government this month — the first since the nation’s municipal-debt meltdown in 1997. The state, proportionally the most-indebted in Brazil, is in such distress that it didn’t pay salaries to public workers in July.

Local governments in Latin America’s biggest country are coming under increasing financial stress as the economy heads for its longest recession since 1931 and caps imposed as part of a federal rescue 18 years ago constrain their ability to obtain financing. Their woes are threatening to make matters worse in a country reeling from an expanding corruption investigation and growing calls to impeach President Dilma Rousseff.

“We see a dramatic situation in the local accounts at a time when the country isn’t doing great either,” Rogerio Braga, a partner at asset management firm Quantitas Gestao de Recursos SA, said from Rio Grande do Sul’s capital city of Porto Alegre. “It’s one problem on top of another.”

Rio Grande do Sul, which borders Uruguay and Argentina, is Brazil’s fifth-biggest state and has a population of 11 million. The state has 62 billion reais ($17.9 billion) of total debt, and the federal government is its largest creditor.

‘Complete Incapacity’

Governor Jose Ivo Sartori and local finance officers went to Brasilia on Aug. 12 to hold talks with Treasury Secretary Marcelo Saintive, according to a statement on Rio Grande do Sul’s official website.

The state is incapable of honoring any of its obligations, state Finance Secretary Giovani Feltes said at a press conference in Porto Alegre on Aug. 8.

“This is the result of a deep misalignment of public accounts,” he said.

Brazil’s Treasury has executed contract guarantees on Aug. 19 relative to the debt by retaining taxation revenue that is supposed to be transferred from the federal government to Rio Grande do Sul.

The state has already spent 26.8 billion reais this year, more than any full year between 2004 and 2009. About a quarter of the outlays went to pay retired public employees.

“The local government basically doesn’t know where to find money anymore,” said Darcy Francisco Carvalho dos Santos, a consultant specializing in public finances who was an auditor for Rio Grande do Sul in the 1990s. “The tendency is for the situation to get worse.”

Bond Ban

The states of Mato Grosso do Sul and Sergipe have also delayed payments to the federal government that were due July 30, newspaper O Estado de S.Paulo reported Friday, citing Brazil’s Treasury.

The debt of states and municipalities swelled to about 12 percent of Brazil’s economy at the end of May, the highest in more than five years, according to central bank data.

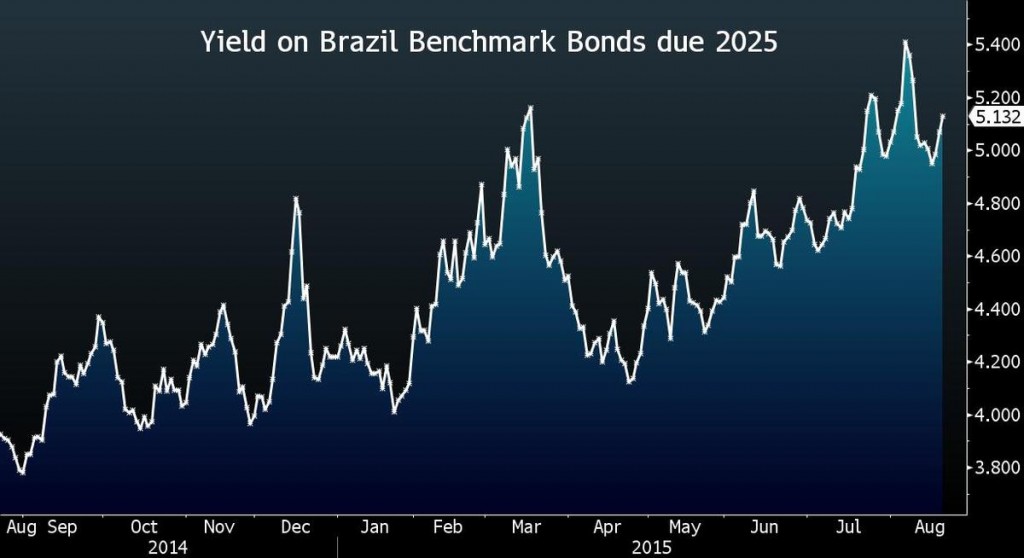

Deepening concern over Brazil’s finances has already caused its borrowing costs in the bond market to surge to a six-year high this month.

After profligate spending and hyperinflation plunged states and cities into default in 1997, the federal government banned them from selling bonds to finance themselves as part of its bailout.

Still, Rio Grande do Sul’s troubles are evident in the bond market. The $775 million ofnotes due in 2022 issued by Banco do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul SA, which is controlled by the local government, declined 0.6 cents to a record low 81.9 cents on the dollar as of 1:55 p.m. in New York. They have plunged 14 percent since the end of July, dwarfing the 1.1 percent average slump in emerging markets.

Yields on the debt have now soared to 11 percent.

“It is a clear situation in which the problems of the state are contaminating trading with the bank bonds,” Quantitas Gestao de Recursos’s Braga said.

Impeachment Calls

Brazil’s deteriorating finances and deepening economic contraction prompted Moody’s Investors Service to cut the government’s rating to the cusp of junk this month, the second downgrade since Rousseff took office in 2011.

More than half a million people took to the streets in Brazil on Aug. 16 to denounce corruption and economic mismanagement in her government. An Aug. 4-5 Datafolha poll showed her popularity among Brazilians sank to 8 percent, with more than two-thirds saying they support impeachment.

And for the first time, analysts began forecasting that the economy will shrink this year and next.

“States are suffering a lot with a more challenging economic scenario for Brazil,” Paulo Fugulin, an analyst at Fitch Ratings, said from Rio de Janeiro. This is “a situation that has been deteriorating for a while and that won’t be solved in the short to medium term.”