RIO DE JANEIRO, Brazil — Think about carbon dioxide emissions and you’ll probably picture a couple of things: smoke belching from a factory or power plant chimney, maybe? Or foul exhaust spewing from a truck’s tailpipe.

That’s entirely correct. Factories, power plants and vehicles produce a lot of the harmful gas going into our atmosphere. In the United States, for example, electricity generation, transportation and industry accounted for 79.5 percent of all greenhouse gas emissions in 2013, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

But Brazil’s a bit different.

It’s the world’s seventh-largest producer of greenhouse gases (if you include the European Union as one producer). But much of this country’s emissions come not from cars and factories, but primarily from what local nonprofit Climate Observatory identifies as land-use change. Put simply, that means cutting down or burning trees to make way for things like crops and cattle.

Saving the forests has become a more important part of the climate debate. It was a crucial discussion point over the agreement signed in Paris in December. And arguably nowhere is this discussion more important than Brazil, home to the largest rainforest on Earth.

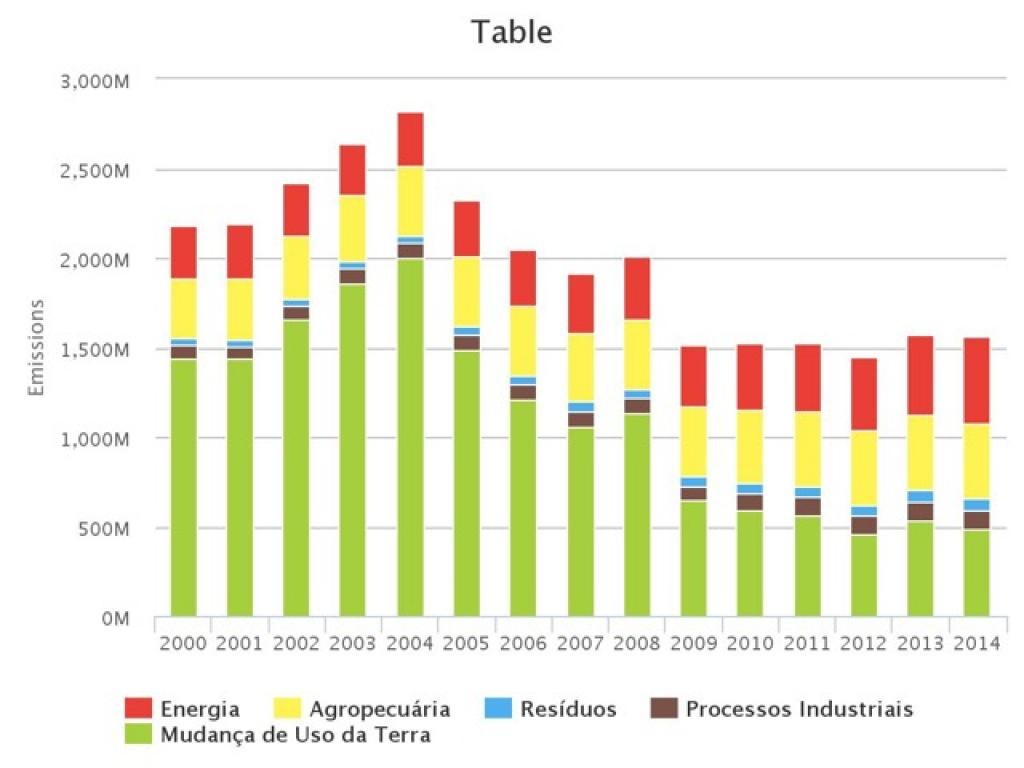

Deforestation and agriculture have accounted for the bulk of greenhouse emissions in Brazil for at least the last decade. Here’s a chart from the Climate Observatory’s Greenhouse Gas Estimate System (SEEG):

The green part of the bars is deforestation. The yellow part is agriculture, red is energy, brown is industrial processes and blue is waste. Transportation doesn’t even show up here (something anybody visiting Brazil’s traffic-choked cities may find hard to believe).

That breakdown makes Brazil’s role in reducing harmful gas emissions pretty different from many other industrialized countries. To reduce the bulk of their greenhouse gases, most industrialized nations have the task of cutting back on fossil fuels through better energy efficiency and cleaner energy sources, like wind and solar.

Brazil, essentially, needs to stop cutting down or burning trees.

But the fact that most of Brazil’s greenhouse gases stem from deforestation gives some environmentalists hope that this country can meet its lofty emission goals.

In September, Brazil committed to cutting its climate emissions by 37 percent below 2005 levels over the next decade and 43 percent by 2030.

For the US, China, or just about any other major emitters, that would be a pretty tough goal. The US has pledged to reduce emissions by 26-28 percent by 2025. China has pledged that its emissions will peak by the same year.

Go back to that chart above. In 2014, deforestation accounted for 31 percent of Brazil’s total greenhouse gas emissions. In other words, to meet its goals, Brazil doesn’t really need to cut down on industry or energy production or transport. It has to protect that hugely valuable carbon goldmine: the Amazon Rainforest.

Curbing deforestation is no cakewalk, however, as Brazil’s history shows. And there are some recent alarming statistics and political maneuverings that place this country’s emissions goals in jeopardy.

Brazil allowed forest clearing at alarming levels in the early 2000s as its economy quickly grew. Then, under increasing international pressure, the Brazilian government implemented policies and practices to curb deforestation through the mid-2000s.

That effort was largely successful, which is why the green portions of that chart have shrunk. According to SEEG data, deforestation last year produced less than a quarter of the greenhouse gas emissions it did in 2004.

But deforestation here climbed in 2013 and 2015, according to the Environment Ministry. Some environmentalists claim that Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff is preaching protection of the Amazon while allowing conditions on the ground to deteriorate.

Moreover, Brazil’s congress is currently dominated by conservative lawmakers who critics like to call the “bullets, beef and Bible” caucus. Without strong opposition from Rousseff, who is busy fighting for her own political survival, some environmentalists worry that the gains of the past decade will be rolled back by pro-agriculture policies that would shrink the forest.

A recent report by Brazil’s National Space Research Institute underscored how crucial the Amazon will be for the country to meet its lower emissions objective.

“The region’s future remains very uncertain,” Brazil’s space agency quoted its Amazon land use researcher Ana Paula Aguiar as saying. “While deforestation rates in the Amazon region have fallen since 2004, they have stabilized at around 6,000 square kilometers per year over the past five years. Will they fall further, stabilize or rise again?”

Other Brazilian scientists remain positive about the country’s long-term commitment to reducing emissions.

“The target they put forward is extremely safe,” said Marcia Rocha, a Brazil analyst at Climate Analytics, a nonprofit research group. “Without implementing any new policies, and by just doing very, very little they will meet the target.”

Rocha pointed out that Brazil’s economy, which is currently stagnating, will also have a large role to play in what happens to emissions rates.

During boom years, Brazil’s emissions tend to peak, as companies exploit the rainforest and consume more energy and raw materials. Right now, the silver lining to Brazil’s dismal economy is the likely dip in emissions that will result, Rocha said. But she worries how long that will last.

“Even when we have a recession like we’re having now, it’s usually followed by a big boom so you actually catch up (on emissions),” she said. “What actually matters for the climate are long-lasting measures.”