Brazil vice-president Michel Temer has launched a new liberal economic policy platform for his party that represents a radical break with the left-leaning programme of Dilma Rousseff, the country’s president.

The move illustrates a widening split between Mr Temer’s PMDB, Brazil’s largest political grouping consisting of mostly conservative regional politicians, and its official ally, Ms Rousseff’s ruling Workers’ party, or PT.

Mr Temer will put the programme, which reads like a wishlist for markets and investors with proposals to liberalise industrial relations and reform pensions and government spending, to a PMDB party congress for adoption on Tuesday.

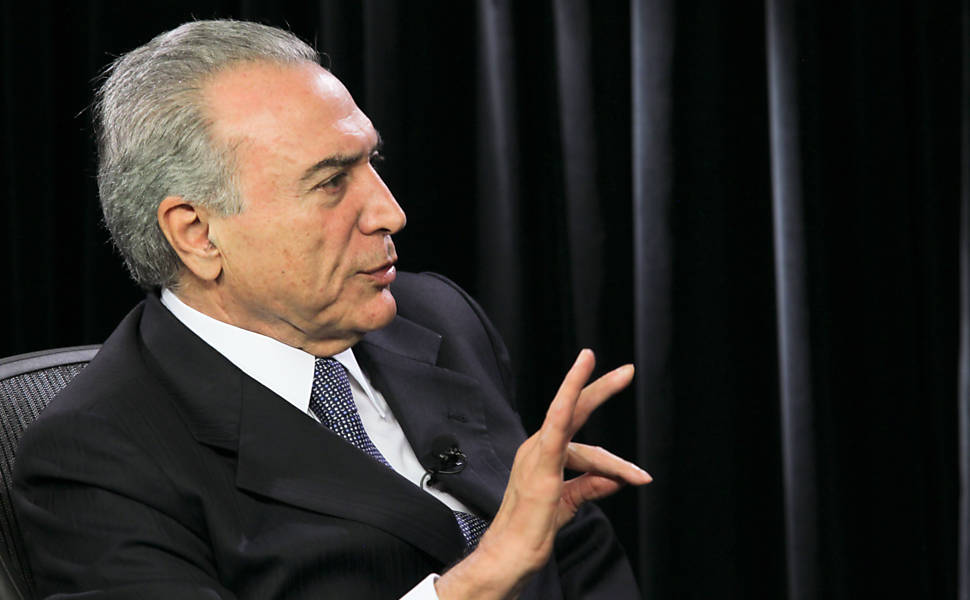

“This is a document from the party for the nation,” the 75-year-old Mr Temer, who is also PMDB president, told the Financial Times in an interview at his offices in São Paulo. “If the government wants to apply these ideas, it can apply them. This is not a programme for or against the government.”

Analysts said the new platform was aimed at shoring up the PMDB’s economic credentials ahead of municipal elections next year and presidential polls in 2018 or in case Ms Rousseff was impeached.

She is suffering from record-low approval ratings, with the economy set to sink 3 per cent this year as part of what is emerging as Brazil’s worst recession since the 1930s.

The launch of the programme, entitled A Bridge to the Future, might also be an attempt to recover some of the PMDB’s lost credibility from corruption scandals, analysts said. Two of the party’s most senior figures, Renan Calheiros and Eduardo Cunha, the heads of the senate and lower house of congress respectively, are being investigated in a corruption scandal at state-owned oil company Petrobras.

“It [the document] is clearly a sign from vice-president Michel Temer presenting himself as an alternative in view of a possible impeachment of the president,” wrote Cristiano Romero, columnist with Valor Economico, a Brazilian business newspaper.

In the interview, Mr Temer was dismissive of any suggestions the platform was related to impeachment or that an impeachment was likely.

Instead, he said the programme was aimed at addressing Brazil’s structural problems and elevating the political debate to discuss the national interest, including within his own party, which he said had lost direction.

One of Brazil’s oldest parties, the PMDB has played a supporting role to the country’s past three presidents without having put forward strong candidates of its own in national elections.

“Today, the PMDB has nothing to say and has to keep falling back on its past achievements . . . we want to change that,” he said.

In its platform, the PMDB proposed making flexible mandatory spending limits in the budget on areas such as health and education that are obligatory under the constitution. Mandatory spending accounts for up to 90 per cent of Brazil’s budget and makes it difficult if not impossible to make cuts in hard times.

As part of this, the document recommends the government adopt “zero-based budgeting” — a practice common in the private sector and made famous by Brazil’s richest man, Jorge Paulo Lemann, who uses it in AB InBev, his beer empire.

Under this system the government each year would be required to evaluate from scratch its expenses and programmes to see whether they were justified and it could afford them. The process would be supervised by a joint congressional and presidential body.

The aim was to avoid a budget deficit of the kind now threatening to blow up Brazil’s finances. The deficit, this year forecast at more than 9 per cent of gross domestic product, is rapidly driving up government debt.

Other proposals included making Brazil’s rigid labour laws more flexible to allow direct wage negotiations between employers and their workers and reforms to the minimum retirement age to stop an explosion in unfunded pension liabilities.

Indexation of pension and other payments to rises in the minimum wage would be scrapped, as would nationalist laws in the oil sector.

On whether the PT would approve the changes, Mr Temer said: “I don’t know.”

But he said Brazil had evolved following the end of military dictatorship in 1984 to democracy and then the establishment of a new middle class in recent years.

“This new middle class has come to demand more of the country,” he said.