5/19/2014 @ 9:38AM |

The Internet is a global and borderless network with nearly 3 billion users, but individual governments are undermining the Net’s foundation by extending the reach of their local laws to Internet companies worldwide. Europe’s highest court shocked the technology industry last week by ruling that Internet search engines must self-censor search results in certain circumstances to comply with the EU’s data privacy law. And last month, Brazil foisted different data privacy rules on any Internet company with one or more Brazilian users (regardless of the company’s geographic location). This ever-growing thicket of Internet regulations threatens the free and open Internet as we know it.

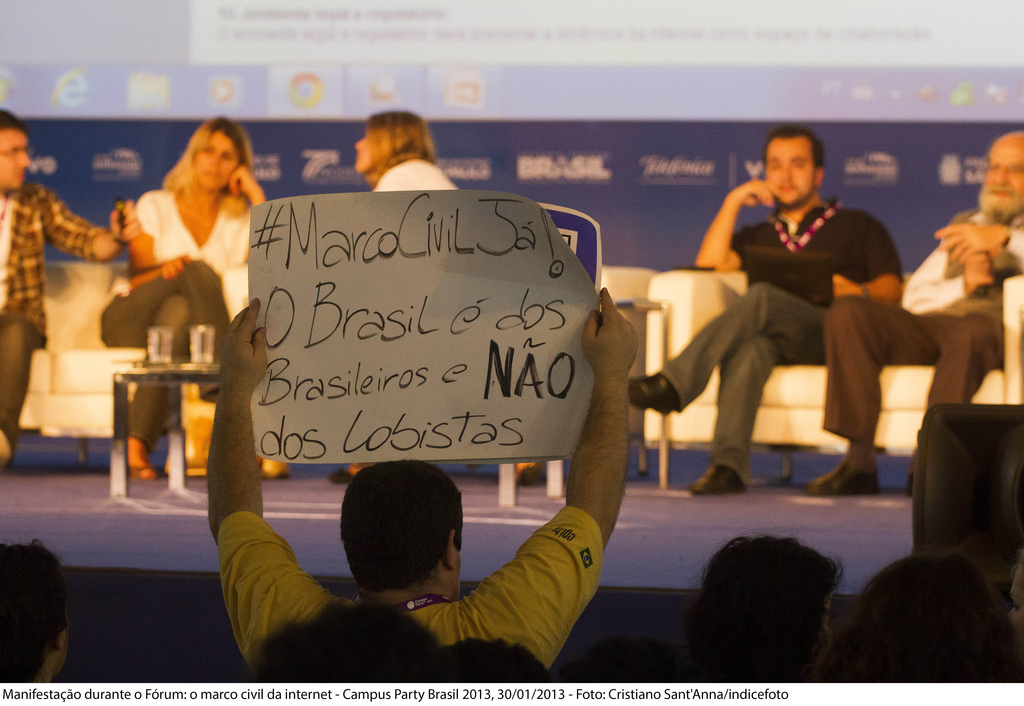

Last month, on April 24, 2014, Brazilian President Dilma Rouseff signed into law the Marco Civil Da Internet, touted as the Internet “Magna Carta.” It contains several business-friendly provisions that ensure network neutrality and protect companies from intermediary liability (i.e. websites are generally not liable for third party content posted on their sites). But it also obligesInternet businesses – ranging from social media sites to online marketplaces – to follow certain privacy rules, and also mandates how they store and share users’ information. Most importantly, the law explicitly applies to any company anywhere that has at least one Brazilian user, has servers located in Brazil, or operates an office there, or effectively, all Internet companies on Earth.

Failure to comply can result in fines of up to ten percent of Brazil-origin revenues or service blockage in Brazil. Once the law enters into effect next month, a Silicon Valley-based firm could, for example, be penalized for complying with U.S. data protection laws that conflict with the Marco Civil. The law provides no guidance – or options – for the many transnational companies that will face competing regulations.

Last week, on May 13, 2014, the European Court of Justice (ECJ) even more problematically ruled that Internet search engines – such as Google or Microsoft — must remove links to third party content from search results where an individual’s privacy interest outweighs the public’s need for that information. This so-called “right to be forgotten” was articulated in response to a Spanish citizen’s suit against Google for not removing links to old (but at the time accurate) Spanish newspaper announcements that he claimed violated his privacy.

Despite vocal criticism of the ECJ’s dubious legal reasoning, Google and Microsoft must now design internal procedures to translate the ruling into an actual process to evaluate and implement users’ removal requests. At what point does an old bankruptcy proceeding become private information? Is the standard different if the information pertains to a criminal conviction? What if the subject of the information is a celebrity? And what if anything happens if a user runs for public office after having the links taken down, effectively masking their past from voters? An ex-politician who previously misbehaved in office and a convicted pedophile have already petitioned Google to remove links to news articles about them.

These are but a few of questions that search engines will confront, each of which will require new systems, immense legal and technical expertise, and other resources. Moreover, the costs to technology companies will increase as the number of different rules increases due to each EU member state interpreting the ruling differently. Given the vagueness of the ECJ decision, this is all but assured, and could even lead to venue shopping where individuals seek out the most favorable country within Europe to bring their complaint.

The task now falls to the EU’s 28 member state data privacy regulators and courts to interpret and implement the ruling. While the reach of the ruling is unclear – unlike the flagrant extraterritorial ambitions of Brazil’s Internet Law – the ECJ did affirm that the fact that Google’s servers being housed outside of Spain does not excuse the company from compliance. Still, it remains unclear if the ruling applies only to searches carried out in Europe or also searches made outside Europe but about EU citizens.

It is not difficult to imagine a scenario in which searches conducted from Brazil, for example, include links to “private” information that would be censored from search results in Europe. Will the EU attempt to apply its data privacy rules to protect information about EU citizens regardless of where the search is conducted? If so, this would in turn potentially violate American free speech protections if the search was conducted in the United States. In short, the quagmire of likely resultant legal conflicts is hard to exaggerate.

As more and more countries follow the EU and Brazil’s lead, Internet companies will have to navigate an increasingly bewildering web of conflicting Internet rules. Technology investment may flee some jurisdictions as administrative burdens increase; this is especially likely in smaller markets where compliance costs are more difficult to justify. Governments must resist the urge to apply their laws extra-territorially because doing so inevitably weakens the Internet. For the network of networks to survive, it must retain its fundamentally international foundation and not be carved up by short-sighted local laws.