KV Kamath, who heads the New Development Bank (NDB) set up by the Brics group of nations with a paid-up capital of $50 billion–contributed in equal proportions by Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa–is uniquely qualified to lead a new financial institution such as this in its formative years: He has worked at a multilateral development bank (MDB), the Asian Development Bank, a national development bank, ICICI and a commercial bank, ICICI Bank.

Based in Shanghai, Kamath is in Goa for the Brics Summit and was enthusiastic about the prospects of rapid development in the Brics nations and of the bank he leads in enabling such development, when ET caught up with him.

Lean, and anything but mean – that is his vision for NDB. In fact, that is part of what is new in the NDB’s nomenclature, he explained. Traditionally, the cheques issued by MDBs came with a note: Please Find Attached, and that attachment was a heavy load of policy prescriptions not always suited for the recipient country. NDB, in contrast, will transfer, along with funds, knowledge.

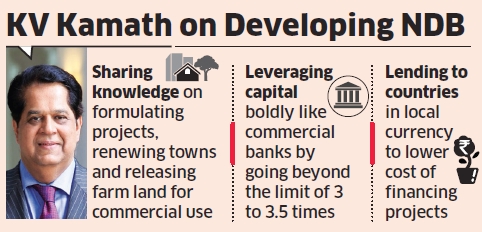

There is plenty of knowledge in the individual Brics nations that has to be shared with others. On how to formulate projects that do not go on and on like Saas-Bahu serials but get completed on schedule and within budget. On how to renew existing towns, expand towns and build new towns. How to release farm land for commercial use.

The point is to share this knowledge on different aspects of developing large countries with others.

NDB will play a big role in this. Drawing on his varied banking experience, Kamath wonders why MDBs limit themselves to a leverage of 3-3.5 times their capital, when commercial banks, with a capital adequacy norm of 11% of assets, have a leverage of nine times.

This is all the more perverse when you consider that a commercial bank lends to risky borrowers whereas MDBs lend to sovereign governments. Not that he will jack up NDB’s leverage to nine times its capital. It has just about begun the process of raising capital now.

It recently issued yuan bonds worth $450 million in China, the issue being oversubscribed three times. It plans to raise $250 million by issuing masala bonds denominated in rupees in the first quarter of calendar 2017, followed by local currency issues in South Africa and Russia next year.

Why this fetish for raising local currency debt? Lending to countries in their local currency is a key element of NDB’s strategy of lowering the total cost of financing projects for recipient countries.

Even if a country gets a dollar loan at a 3.5% rate of interest, by the time it repays the loan, the interest cost typically mounts to the high teens, says Kamath, thanks to depreciation of the local currency. If the loan comes in the local currency in the first place, currency risk drops out of the picture.

How will the NDB tackle project delays? Kamath believes that all the Brics nations have the capacity to develop reasonably well-articulated projects with realistic timelines for implementation. The trouble is, he believes, when regulation and policy suddenly change and create obstructions for the project.