The Separate Amenities Act might sound like an innocuous measure covering the remit of an obscure local council. It was, in fact, one of the most pernicious laws ever devised by the old South Africa, allowing the country’s white overlords to segregate every public facility – parks, buses, beaches, even lavatories – according to race.

And 25 years ago today, the very parliament which had passed this law voted to repeal the Act and consign its handiwork to oblivion. This debate in the National Assembly in Cape Town was the moment when South Africa under FW de Klerk began to sweep away the legal edifice of apartheid.

As those blows were struck, ordinary South Africans believed that the struggle against apartheid was destined to succeed – and that success would mean freedom, certainly, but also jobs and homes and perhaps even prosperity for millions who had been deliberately impoverished by the white regime.

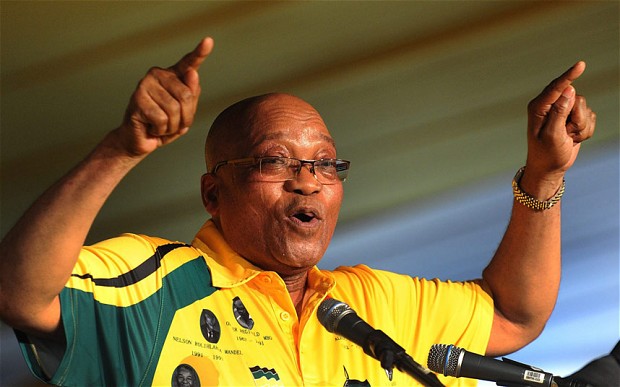

A quarter of a century later, some of that promise has been redeemed. Freedom means that South Africa has an elected leader in Jacob Zuma, who is held to account by independent judges, journalists and a vociferous parliament. He stands at the head of a liberal democracy whose constitution proclaims that South Africa is an “open society” belonging to “all who live in it”.

After the oppression of the past, no-one should undervalue this achievement. And yet 25 years after the apartheid laws began to crumble away, can anyone argue that South Africa under Mr Zuma is upholding the full promise of that moment?

On Monday, a bloodsoaked dictator was allowed to escape justice while visiting South Africa. Omar al-Bashir, who has tormented Sudan for 26 years, was an honoured guest of Mr Zuma at an African Union summit in Johannesburg. Never mind that Mr Bashir has been indicted by the International Criminal Court (ICC) for alleged genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity. Never mind that his armed forces and militias have laid waste to the region of Darfur, butchering countless Africans.

And never mind that South Africa is legally obliged to arrest Mr Bashir and ensure that he stands trial, in accordance with its membership of the ICC. Instead, Sudan’s autocrat was able to enter the country, attend the summit and then fly home unmolested. Most remarkably of all, the High Court had ordered the government to prevent Mr Bashir from leaving South Africa, pending a decision on whether to demand his arrest. But the evidence suggests that Mr Zuma’s government, at the very least, turned a blind eye to the court order and allowed Mr Bashir to depart on a private jet.

South Africa might have an impeccably liberal constitution, but this week its rulers chose to ignore domestic and international law in the cause of permitting a tyrant to escape justice. This is the same country, incidentally, which refused to grant a visa to the Dalai Lama last year, apparently to avoid upsetting China. Mr Zuma has reached the extraordinary position where he will spurn a Nobel Laureate, but welcome a dictator. Moreover, the president will do so even if the tyrant in question is wanted for the worst of all crimes and the law obliges his arrest. There, in a nutshell, lies Mr Zuma’s betrayal of the ideals of a new South Africa.

What did he stand to gain by welcoming Mr Bashir? South African foreign policy is hard to understand, but solidarity with African leaders – particularly those who are on bad terms with the West – appears to come before everything else, including international justice. In fairness, that tradition predates Mr Zuma. During his presidency, Nelson Mandela embraced various pariahs, ranging from Colonel Gaddafi of Libya to President Suharto of Indonesia. Thabo Mbeki famously became a defender of Robert Mugabe, reducing himself to the role of cheerleader for the latter’s destruction of Zimbabwe.

What sets Mr Zuma apart, however, is the sense that he is not only wayward, but directionless. It is not so much that he is a president with the wrong ideas, but that he has no ideas. As a result, he is failing to redeem the second half of the new South Africa’s promise, namely that freedom would also bring sustained improvement to the lot of the poor.

Today, South Africa’s economy is stagnant, with growth running at an annual rate of just 1.3 per cent. That matters a great deal because the economy needs to expand by at least 5 per cent every year if poverty and unemployment are both to fall. Instead, the number of people out of work has risen by 1.6 million since Mr Zuma won the presidency in 2009. Unemployment – even at the narrowest definition – now stands at 26 per cent. If you use a broad definition that includes people who are too demoralised to look for work, the jobless total rises to 36 per cent.

On their own, those numbers go a long way towards explaining why South Africa suffers so terribly from violent crime and why shanty towns still surround every city. Once, the people of those townships would demonstrate against apartheid; today they mount regular protests against the woeful delivery of basic services by corrupt and underfunded local councils.

Governments cannot create jobs or prosperity, but they can remove some obstacles. Sadly, Mr Zuma has helped to impose new constraints such as the electricity blackouts which have become routine in Johannesburg, the commercial capital. These are happening because old power stations have shut down, causing a wholly predictable loss of capacity. The government ignored the warning signs for a decade or more, leaving the business of generating electricity in the hands of Eskom, a run-down state utility without the money to build new capacity.

What is needed is a bold policy decision to allow the private sector to invest. But clear and bold decisions are exactly what Mr Zuma specialises in avoiding. His particular model of leadership means that South Africans will probably have to get used to blackouts.

Instead of grappling with these problems, Mr Zuma spends his time fending off a swirl of scandal and intrigue. Before he became president, he faced a battery of criminal charges amounting to no less than 783 counts of alleged corruption, fraud and racketeering. He always protested his innocence, but the charges were quashed on procedural grounds without being tested in court. As a result, South Africans were denied the chance to learn the truth about their leader, one way or the other.

Even while the crime-ridden shanytowns endure, the government recently found more than £13 million of public money to spend on Mr Zuma’s private homestead at Nkandla. He explained that the cash went on “security upgrades” necessary for his job. It turned out that his idea of “security” included the taxpayer funding his swimming pool, cattle kraal and chicken coop.

When the apartheid laws began to be repealed in 1990, Mr Zuma was about to return to South Africa after almost 20 years of imprisonment or exile. More than two decades later, it is South Africa itself that is imprisoned by his stultifying rule – and the hopes of countless millions that lie tattered and torn as a result.